RCEP signed, reviewing Japan’s Asian policy during the Cold War (I)

With the RCEP agreement finally settled this month, the economic and trade relations between East Asia and Southeast Asia will become closer in the foreseeable future. Under the background of the successful election of US Democratic candidate Biden in the 2020 presidential election, Japan, as the current leader of CPTPP and a signatory of RCEP, its diplomatic choice in the future is also of concern. Will Suga Yoshihide’s cabinet follow the trend and emphasize economic and trade cooperation with countries in Asia, or will it return to its foreign policy during the Obama administration of the Democratic Party and seek coordination with the east coast of the Pacific through the TPP framework? At present, when the argument of the new cold war is raging, we may be able to glimpse some clues of Japan’s current decision-making by reviewing Japan’s diplomatic choices in the cold war between the United States and the Soviet Union in the twentieth century.

As we all know, Japan and China did not establish formal diplomatic relations for a quarter of a century from 1949 to 1972. Although the two countries managed to develop and maintain some trade.【1】However, under the background that the United States pursues a containment policy towards the communist countries in Asia, Japan’s contact policy with China, Vietnam (North Vietnam) and even countries that pursue neutrality in Southeast Asia has experienced considerable repetitions. However, Japan’s economic assistance to pro-American countries in the region, such as Indonesia after Suharto’s coup in 1965 and Malaysia, which suppressed its own communist struggle for a long time, has long been regarded by scholars in the history of international relations as evidence that Japan follows the American policy in Asia.

However, with the gradual declassification of diplomatic documents from 1950s to 1960s, the assertion that Japan was simply classified as a follower of American containment strategy in the past was questioned to a considerable extent. Through these diplomatic documents, we can see that many of Japan’s early engagement policies with China, such as breaking the trade ban on China (CHINCOM) and providing export loans to China through state-owned export-import banks, directly challenged the American strategy in Asia. At the same time, Japan’s strategic conception in Southeast Asia, that is, the strategy of establishing Japan-Southeast Asia manufacturing industry chain, is also obviously opposed to the American conception of Japan as a supplier of consumer goods in Southeast Asia. The author also wants to point out that this opposition not only appeared in the cabinet of Ichiro Hatoyama and Ikeda Hayato, which were relatively pro-China and neutral, but also appeared in the cabinet of Kishi Nobusuke and Eisaku Satō, which were traditionally considered pro-American and anti-China. In other words, the pursuit of post-war Asian policy independence is the consensus of the Japanese ruling group and will not change because of the change of Japan-US relations. In this paper, the author will sort out the diplomatic documents between the United States and Japan from the Bandung Conference in 1955 to the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Japan in 1972 to illustrate Japan’s entanglement and hesitation in the pro-American/independent diplomatic routes. The upper part will mainly describe the diplomatic confrontation between China, Japan and the United States before the Bandung Conference in 1955 and the Sino-Japanese LT Trade Agreement in 1961, while the lower part will mainly describe the political turmoil in Southeast Asian countries since 1960, as well as the influence of different routes of struggle between Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of International Trade and Industry on Japan-US foreign policy.

Sino-Japanese Contact in Bandung Conference in 1955 and Japan’s Idea of "Returning to Asia"

If we try to find the origin of Japan’s postwar foreign policy toward Asia, a historical node that can hardly be ignored is the Bandung Conference, which we are all familiar with, that is, the 1955 Asian-African Conference. Apart from the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence put forward by China at the Bandung Conference, Japan also got the opportunity to intervene in regional politics again through this conference. Despite the strong opposition from the United States, Ichiro Hatoyama’s government sent a Japanese delegation headed by Tatsunosuke Takasaki, then Japan’s Minister of International Trade and Industry, to attend the meeting, and took this opportunity to realize informal contacts between China and Japan.

The Japanese delegation is headed by Tatsunosuke Takasaki (second from left).

Japan’s diplomatic decision to participate in the Bandung Conference was made against the background of its domestic economic recovery. With the smooth progress of Japan’s economic recovery in the mid-1950s, when Ichiro Hatoyama became prime minister in 1955, Japan had generally returned to the highest level of the pre-war economy. Hatoyama confidently declared in Congress that Japan’s "post-war era" was over. In his view, the urgent task of the Japanese government is to re-establish Japan’s position in the international community and conduct diplomacy that is more in line with Japan’s interests. Under the guidance of this thought, Ichiro Hatoyama’s government hoped to adopt a softer diplomatic stance, and put forward the idea that Japan would intervene in Asian geopolitics as a "window between the East and the West".

On the other hand, in 1955, China also had a political basis for seeking cooperation extensively in diplomacy. It is true that both the War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea in 1951 -1953 and the efforts of China’s military advisory group headed by Chen Geng in Dien Bien Fuk’s triumph in 1954 clearly showed that China would be committed to opposing the imperialist intervention of western countries in neighboring countries. However, when the war ended in 1953, the demand for resources necessary for domestic economic construction through foreign trade made China leaders adopt a very pragmatic diplomatic attitude on the international stage. European delegates to the Geneva Peace Conference in 1954 were surprised to find that China had adopted a foreign policy that was different from the previous one and centered on the economy. Similarly, at the Bandung Conference in 1955, Zhou Enlai also put forward suggestions for economic cooperation to Indonesian, Ceylon and Cambodian representatives, and promised that China would not seek interference and influence other countries’ internal affairs.

It is worth mentioning that the candidates for the Japanese delegation to the Bandung Conference are worth pondering, and can also reflect Japan’s consideration of its international status at that time to some extent. Tatsunosuke Takasaki, the head of the delegation, was appointed as the chief representative of Japan by Ichiro Hatoyama, not only because he has extensive contacts in the industry as a practical economic bureaucrat, so that he can represent Japan to discuss economic and trade cooperation with the countries present, but also reflects the long-standing Pan-Asian tradition in Japan. Whether it is the ruling Liberal Democratic Party after the war or the Japanese industry, before Japan’s defeat and surrender in the first half of the 20th century, quite a few people participated in Japan’s aggression and expansion in Southeast Asia, China and the Korean Peninsula, and were influenced by the so-called "Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Circle" theory, so they had intuitive feelings and experiences on the economic integration of Japan and Asia. Because the United States relaxed its responsibility for the old Japanese decision makers in Germany and Japan for the needs of the Cold War after the war, these former decision makers who were once expelled as war criminals from politics and business were able to once again enter the decision-making level of Japan. No matter Tatsunosuke Takasaki in politics, Kishi Nobusuke and Masayoshi Ohira, who became prime ministers after Hatoyama, Yoshisaburo Higasaki, the foreign minister in the Shore Cabinet, or Kaheita Okazaki and Yoshisuke Yukawa in industry, they all participated in Japan’s actions to support the puppet Manchukuo and Wang puppet regimes as economic bureaucrats during the Japanese invasion of China. These people who worked in the Puppet Manchukuo and Manchuria Railway Corporation formed a "Manchurian network" group across the political and business circles in Japan because of their common experience after the war.As the members of this group came back to power with the acquiescence of the United States after the war, Japan’s pre-war concept of pan-Asianism regained its influence in the decision-making level. In other words, Japan’s diplomatic inertia formed in the first half of the twentieth century was also continued in Japan’s foreign policy in 1955, which was embodied in re-establishing Japan’s influence in regional affairs by emphasizing "returning to Asia". Therefore, Takasaki’s participation in the Bandung Conference on behalf of Japan can be described as the epitome of this strategic consideration at the personnel level.

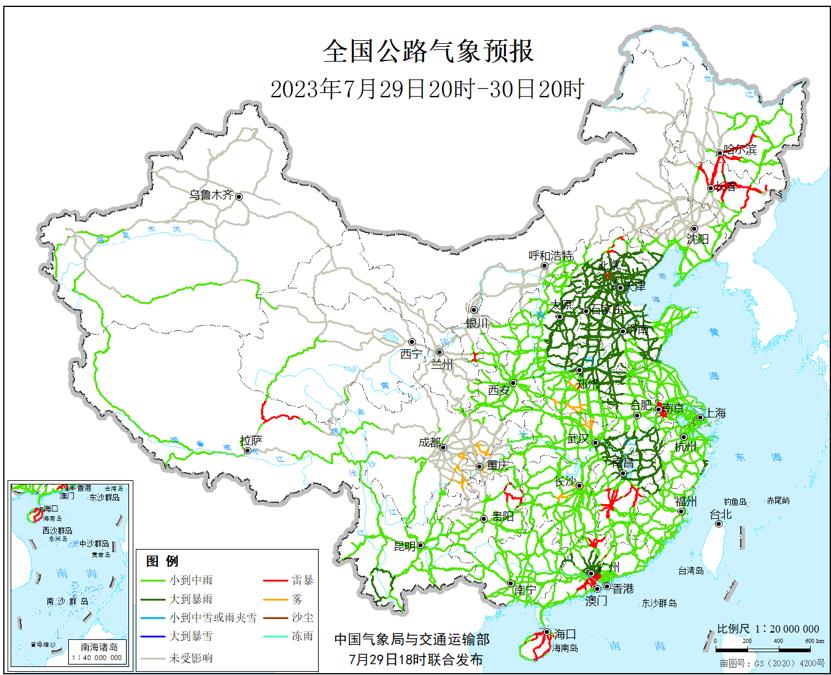

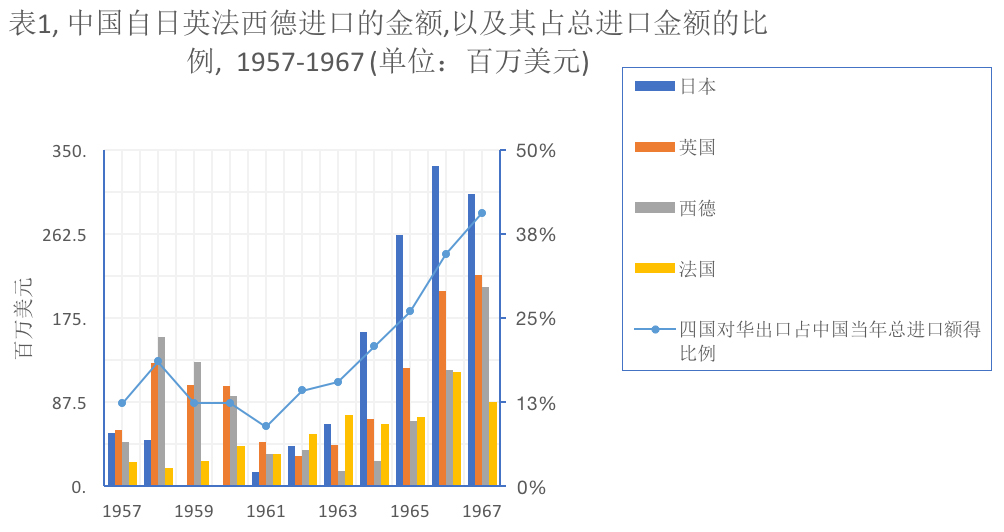

Of course, Takasaki cannot be simply classified as a supporter of the old Japanese policy. In Japan’s post-war political map, the most striking feature of Takasaki is that as a promoter of "diplomacy with communist countries"-Takasaki also participated in Japan’s diplomatic coordination with the Soviet Union, and participated in and promoted the negotiation of Japan-Soviet fishery agreement with Soviet Deputy Prime Minister mikoyan for three times in 1956, 1960 and 1962. At the Bandung Conference, Takasaki seized the opportunity to hold two secret talks with Premier Zhou Enlai, who also attended the conference, and reached a consensus on Sino-Japanese trade and civil goodwill. This has also become an important basis for Japan’s contact with China after 1955. After Bandung, China and Japan shared common interests on the decolonization of Asia and possible economic cooperation in the Pan-Asian region. After the meeting between Zhou Enlai and Takasaki, the two countries made serious efforts to deepen economic ties. In 1957, Japan and China signed two agreements, allowing China to export raw materials in exchange for industrial products and equipment. Although Sino-Japanese trade was interrupted after 1958 due to the Nagasaki flag incident, the trade between the two countries began to resume in 1961, and Japan became China’s largest import source country in 1964 (Table 1).

Of course, Japan’s performance at the Bandung Conference can not be simply described as "pro-China", but can be the best footnote for the country to wander between pro-America and independence. As early as before the opening of the Bandung Conference, Japanese Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru, with officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, strongly opposed Hatoyama’s decision to attend the Conference. Although Hatoyama insisted on sending a delegation to attend the Bandung Conference in the end, Shigemitsu Mamoru appointed Toshiichi Kakuba of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as the deputy representative of the Japanese delegation. It is precisely because of the communication between Kasai and Shigemitsu Mamoru that the meeting between Takasaki and Zhou Enlai was known by the US, and then pressure was exerted to cancel the third secret meeting between Zhou Enlai and Takasaki originally scheduled during the meeting. In other words, the opposition between pro-American bureaucrats and contact bureaucrats in the Japanese government has caused considerable constraints on the contact policy with China/the Soviet Union that Ichiro Hatoyama’s cabinet has been adhering to.

This contradiction between the pro-American faction and the independent diplomatic faction within the Japanese government is also reflected in the policy level, which is embodied in the Japanese delegation’s dependence on American capital and dollars in the economic proposal at the Bandung Conference. At the Bandung Conference, Japan put forward several economic issues: for example, establishing an Asian Payment Union to introduce foreign capital for Asian economic construction and solve the payment problem in bilateral trade, and establishing a permanent Asian Economic Cooperation Union to discuss regional economic development. This proposal received opposition from China and Indian countries. This is because the Asian Payment Union proposed by Japan will use the US dollar as the reserve currency. In the eyes of India, a former British colony, an Asian system based on the pound will be more beneficial to it. According to the telegram sent by Li Kenong to Ye Jizhuang on April 22, 1955, the representative of China was also deeply worried about the US dollar entering Southeast Asia through this Japanese channel. Li Kenong’s report reflects China’s judgment that whether the payment system is based on British pound or US dollar, it will pose a great threat to the independence of Asian countries. At the same time, due to the lack of sufficient foreign currency reserves, China will fall into diplomatic passivity in any system. At the same time, China is also wary of the possible role of the United States behind Japanese economic expansion in Asia. Zhou Enlai’s report to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China after Bandung Conference clearly reflected this attitude. In Zhou Enlai’s report of April 30th,China believes that Japan’s massive dumping in the Southeast Asian market is supported and encouraged by the US government, and its purpose is to establish economic control over Southeast Asia. In other words, China’s understanding of Japan is based on its awareness that it can’t get rid of being the executor of American Asian strategy whether it is voluntary or not.

Coincidentally, Japanese officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs are also full of anxiety about industrial competition from China: according to the report of the China Division of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs on July 23, 1959, Japanese diplomats believe that the trade competition between China and Japan in the "free countries" in Southeast Asia has become increasingly fierce since 1955. In their view, China’s free aid and cheap exports to Southeast Asia pose a threat to Japan’s market share, and the signing of a series of "barter" agreements, such as the rice-for-textiles agreement between China and Myanmar and the rice-for-rubber trade agreement with Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), is a major challenge to Japan’s trade system based on international money and credit. Judging from these diplomatic documents in the 1950s, there are indeed voices within China and Japan to build each other’s strategic intentions based on the reality of the Cold War.

Japan-US Dispute Centered on Southeast Asian Policy

Then, is Japan, as previously recognized by academic circles, a follower of the United States to exert economic influence on Southeast Asia, thus curbing China’s influence in this region? Traditional academic circles believe that Japan gave up its diplomatic efforts to seek neutrality after the Kishi Nobusuke administration came to power in 1957, and instead expanded Japan’s economic interests in the western camp through the Japan-US alliance, and at the same time expanded Japan’s local economic influence with the help of the expansion of the United States in Southeast Asia. This assertion that Japan’s foreign policy is described as "hitchhiking" widely appears in the works of Japanese and American scholars.【2】. In this understanding, Japan is a staunch supporter of the United States, and the high consistency of interests between the two countries in Southeast Asia is an important cornerstone of this cooperation.

However, this argument has been challenged with the declassification of the latest diplomatic documents: since 1955, Japan has been obsessed with promoting economic integration with Southeast Asia, which is not in line with the national interests of the United States in the eyes of American decision-making groups. In Japan’s view, the key to Japan’s post-war rise lies in industrial transformation, that is, from low value-added manufacturing industries (such as textiles and food processing industries) to high value-added manufacturing industries (chemical industry, steel industry, shipbuilding industry). This process not only needs Japan to open the markets of western countries, but also needs to establish the industrial chains of Japan and Southeast Asian countries, obtain the markets, raw materials and primary processed products from the latter, and export technical standards to integrate them into the Japanese-led economic cycle. However, for the United States, Southeast Asia is the frontier of the struggle with China and the Soviet Union, and it is a neutral zone that may fall to the communist camp like a domino at any time. In the eyes of American policy makers, the support for Southeast Asia must focus on all kinds of direct assistance, such as food and consumer goods that people can directly use and military training and equipment against communist party revolutionaries. In this process, Japan should become a "quartermaster of a democratic country", while the United States, as an "arsenal of a democratic country", provides consumer goods and military assistance to the pro-American regime in Southeast Asia. In this sense, the United States and Japan have quite different ideas about Southeast Asia.

The starting point of this opposition is the Bandung Conference in 1955. The Asian Payment Union and the Asian Development Commune proposed by Japan at the meeting are not without warning. Tatsunosuke Takasaki himself submitted a proposal to Eisenhower as the Minister of International Trade and Industry of Japan before the meeting, seeking the support of the United States for Japan to establish economic cooperation in Southeast Asia. In this diplomatic document issued on March 9, 1955, Takasaki tried to persuade the United States to provide part of the reserve funds for the Asian payment union envisaged by Japan (according to Takasaki’s vision, the payment union needs to inject about 200 million US dollars from outside every year). Another noteworthy Japanese position is Japan’s position as a middleman in the aid sent by the United States to Southeast Asia. In this proposal, Takasaki proposed to the United States that in order to support Japan’s economic development, the United States should hand over American raw materials (such as grain and cotton) to Japan for processing and then transport them to Southeast Asia as food and textiles.

Corresponding to Japan’s active promotion of this plan, the attitude of the United States towards these two proposals is quite cold. Neither Eisenhower’s regime nor Kennedy/Johnson’s regime supported Japan’s plan. In Eisenhower’s view, Japan’s economic integration in Southeast Asia will be a huge waste of American resources: for the United States, which is seeking to curb the expansion of communist regimes on a global scale, instead of providing a lot of funds to support economic diplomacy that cannot be effective in a short time, it is better to use more resources to support countries that clearly express their pro-American stance and prevent these regimes from being overthrown by their own insurgents through direct consumer goods and military assistance. For the U.S. government, which just experienced diplomatic failure to Vietnam at the Geneva Peace Conference in 1954 and increased blood transfusion to the government of Wu Tingyan in South Vietnam after the conference, the Japanese proposal is unattractive.

However, Japan has not given up its idea, but its diplomatic efforts will not change the attitude of the United States in the next few years. In 1957, Ichiro Hatoyama’s cabinet, which adhered to the contact policy, was dissolved, and pro-American Kishi Nobusuke came to power. In that year, he visited the United States to seek American support for his regime. During the negotiation with Eisenhower, Kishi Nobusuke once again put forward the Japanese idea of establishing an Asian payment union, and hoped that the United States would give a clear statement and direct financial support. According to the record of the talks between the two sides on June 19, 1957, Eisenhower flatly rejected Kishi Nobusuke’s proposal and pointed out that "[Although] we understand Japan’s position, the resources of the United States for Southeast Asia are limited. Any support must be realistic and affordable. " Even at the meeting of the Operation Coordination Board on September 25th, Eisenhower Administration directly stated that any idea of establishing a common development fund in Southeast Asia was unrealistic. The differences between the United States and Japan on this issue can be seen at a glance.

The differences between the two sides also extended to the subsequent regimes of the two countries. The signing of the US-Kishi Nobusuke security agreement in 1960 triggered large-scale public protests, which eventually led to the downfall of the Japanese government. Kishi Nobusuke was succeeded by Ikeda Hayato, who was born in the Ministry of International Trade and Industry. It was during Ikeda’s cabinet period that Japan launched the "Income Multiplication Plan" aimed at vigorously promoting the development of the national economy, and made it clear that Japan’s economic development must rely on the output of industries. In 1962, Japan passed the Temporary Measures for the Revitalization of Specific Industries Act, and regarded the export of steel, automobile and oil industries as Japan’s core interests. Under this policy, Japan began to actively seek industrial integration with Southeast Asia, and achieved certain diplomatic achievements in the World War II compensation agreement with the government of Su Jianuo, Indonesia, that is, by compensating Japanese-made equipment, helping Indonesia to train technicians, and providing interest-free/low-interest export credit to purchase Japanese equipment, the export of Japanese industrial technical standards was realized.

For the United States, Japan’s economic development is commendable, but its vision for Southeast Asia does not meet expectations. In 1961, Rusk Dean, Secretary of State of the Kennedy Administration, visited Japan and held consultations with Japan for several days in Hakone. During the consultation on November 3rd, Eisaku Satō, then Japanese Minister of International Trade and Industry (later Prime Minister) and Kenji Fukunaga, then Japanese Minister of Labor, made sharp questions to the US side, questioning the rationality of the US policy towards Southeast Asia. The former accuses the United States of being meaningless in supporting Southeast Asia except "helping some regional leaders to build their own statues", while the latter demands that rusk clearly explain the position that the United States regards Japan as its Asian policy "agent". During the three-day consultations, Japan’s attitude was very clear: the United States should abandon its rigid Asian policy and fully accept Japan’s proposition of economic integration in Southeast Asia.

In contrast to Japan’s questioning, the United States has never given in to its position. Deputy Secretary of State Fuller and Freeman rejected Japan’s proposal to develop supporting industries of heavy chemical industry in Southeast Asia, but stressed the need to support agriculture and light and small industries in Southeast Asia. Rusk pointed out more bluntly that if Japan wants to continue to be an intermediate country of American aid to Southeast Asia, it must follow the position of the United States and only give aid funds to regimes with clear pro-American and anti-communist positions. At the same time, Japan’s contacts with neutral countries such as Myanmar and Indonesia will not be included in the direct support of the United States. Although this meeting was finally praised as an important achievement in deepening the understanding between the United States and Japan in public reports, the declassified meeting documents exposed the huge differences between the two sides. The differences between the two countries’ positions on Southeast Asia continued until the coup in Suharto in 1965 and the comprehensive escalation of the Vietnam War.

Solution: an analysis of the differences in Asian policies between the United States and Japan

So, what caused the diplomatic differences between the United States and Japan from 1955 to 1965? The author will discuss the internal affairs and regional politics of the two countries respectively. On the one hand, in the markets of developing countries, Japan is facing a common impact from the East and West camps. Whether it is the "barter" trade agreement between China and the Soviet Union and Southeast Asian countries, or the advantages of European and American countries in technology and capital, Japan’s actions to expand overseas markets are facing fierce competition. However, the crisis also contains a huge turning point: with the vigorous development of anti-colonial struggles (which are often led by communists) after the war, new nation-states have sprung up, and there has been a vacuum in the colonial market that was firmly controlled by Britain and France. For these emerging countries, it has become an important demand to get rid of the dependence on the former sovereign state economically and promote industrialization independently. For Japan, the reshuffle of Southeast Asia has become a godsend opportunity to pursue its own industrial upgrading and overseas trade share. From this point of view, it is even more natural for Japan to participate in the Bandung Conference and make friends with China, which has good relations with revolutionaries in Southeast Asian countries.

On the other hand, for Japan, the decade that began in 1955 was also a decade when Japan tried to integrate into the western economic system, and in the process, Japan paid a huge price. Some industries that flourished after the war, such as textiles and organic chemicals, were impacted by the protectionist policies of western countries, which made it difficult to develop in European and American markets. Since 1958, Japan’s textile exports to the United States have even been subjected to tariff repression and anti-dumping investigations by the United States. At the same time, Japan is also seeking to join the western economic clubs, namely the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the General Agreement on Tariffs (GATT). In the negotiations, Japan was explicitly asked to make concessions, open its market to countries in the same camp and stop protecting its industries with tariffs. Japan’s economic liberalization reached its peak in 1965: Sato’s cabinet assured the United States that it would provide Voluntary Export Restriction for Japanese textiles and promised to open 90% of the Japanese market as the price of joining the OECD. In other words, from 1955 to 1965, Japan integrated into the western economic system at great cost, and in order to maintain the competitiveness of Japanese industries, Japan must race against time to cultivate its own industrial alliances in other markets to cope with the competition from Europe and the United States. It is precisely because of this that Japanese industrial giants have also become the main force to promote Sino-Japanese trade negotiations and Japan’s investment in Southeast Asia.Both Kurashiki Silk Weaving Co., Ltd. (today’s Kolili Kuraray Co., Ltd.), a giant in textile and chemical industry, and Hitachi Group, an equipment manufacturing industry, actively supported the policy of engagement with China and Southeast Asia put forward by Japanese economic bureaucrats headed by Takasaki, and even directly participated in the negotiation process.

If for Japan, the postwar foreign policy was mainly influenced by economic factors, then for the United States, the leader of the western camp, it was mainly political factors that influenced its Asian policy in the 1950s. Whether it was the stalemate of the Korean War in 1953 or the military victory of North Vietnam against France under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh in 1954, the United States began to seriously examine China’s geopolitical influence in Asia, and then looked at Southeast Asia with a very conservative and skeptical eye, fearing that a communist revolution would emerge from any Southeast Asian country that swept the whole region.【3】. In the case that Southeast Asia may enter the communist camp at any time, Japan’s proposal to develop Southeast Asia’s industries is naturally inappropriate in the eyes of American policymakers. In contrast, it is more in line with the national interests of the United States in the eyes of American policy makers to directly provide food, consumer goods and military assistance to pro-American countries in Southeast Asia through policies such as the Food for Peace Act (Public Law 480). In this scenario, Japan, as an American ally with the most developed production capacity in East Asia, is naturally entrusted with the task of "quartermaster of democratic countries". From Eisenhower’s regime to Johnson’s regime, such cognition has always had a huge market among decision makers in the State Council, USA. This situation was partially reversed until Nixon came to power and decided to end the Vietnam War and ease relations with China.

Of course, we can’t ignore the influence of European economic integration on Japan. The agreement of the European Economic Community (EEC) between France and West Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, which was signed in 1957, has obvious influence on Japanese policy makers. Not only because of the fierce competition between Europe and Japan in the global market, but also because the industrial integration policies pursued by the European Economic Community (such as jointly regulating agricultural prices, establishing common agricultural funds, and setting industrial standards) coincide with the policy blueprint that Takasaki and others hope to promote in Southeast Asia. In this case, it is not difficult to understand that Japanese policymakers feel a sense of crisis and work harder to promote similar agendas.

Conclusion and Prospect: Japan-US Relations in 1960s: From Disputes to Confluence

So far, this paper briefly combs the differences between Japan and the United States in Southeast Asia policy and China policy from the 1950s to the mid-1960s, and briefly analyzes the factors that may lead to these differences. As mentioned above, with the Indonesian coup in 1965 leading to the fall of the pro-China Su Jianuo regime, the differences between Japan and the United States will be bridged to some extent in the increasingly intensified Cold War confrontation in Southeast Asia, and the relations with China will be deteriorated to some extent. The second half of this paper will continue to trace back to Japan-US policies towards Southeast Asia after 1965, and focus on Japan’s domestic politics, especially the struggle between officials who support independence in the Ministry of International Trade and Industry and those who support coordination with the United States in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. At the same time, it will demonstrate what factors made the pro-American bureaucrats in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs finally overwhelm the technocrats in the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, and forced the latter to give part of the decision-making power to Japan’s foreign trade policy to the former.

[1] Japan signed a non-governmental trade agreement with the Republic in 1953. Before the Nagasaki incident in 1958, Japan signed four non-governmental trade agreements with China, and in 1958, it signed a Sino-Japanese iron and steel agreement to carry out exploratory cooperation in the field of industrial manufacturing. Although the trade relations between China and Japan were frozen after the Nagasaki incident in 1958, China and Japan signed the LT trade agreement through negotiations between Liao Chengzhi and Takasaki Tatsunosuke in 1962. Japan also became China’s largest trading country two years after the signing. This five-year trade agreement was renewed in 1967 and continued until the formal establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Japan in 1972.

[2] Representative scholars who hold this view, such as Chalmers Johnson, Warren Cohen, Miyagi, Tian Feng Long, etc.

[3] This view is often called Domino Theory, which emphasizes that countries with communist revolutions will have a huge demonstration effect on the surrounding areas and give birth to communist revolutions in other regions.